I’ve recently started writing a historical novel. Set in the colony of Victoria in 1874, it features bushrangers, ex-convicts, a kindly and badly-done-by surgeon general and an assortment of other characters.

My mum was a history teacher who taught the history of early white colonial settlement in Australia. Because of her, I’ve been reading books, listening to music and poring over photographs, journals, sketches and paintings from and about that era since I was about 10 so I probably have a handle on the language of that time, just by osmosis. And despite my love of plain language, and having a day job that relies on it, I thoroughly enjoy the density of texts like Rolf Boldrewood’s Robbery Under Arms and other contemporary works.

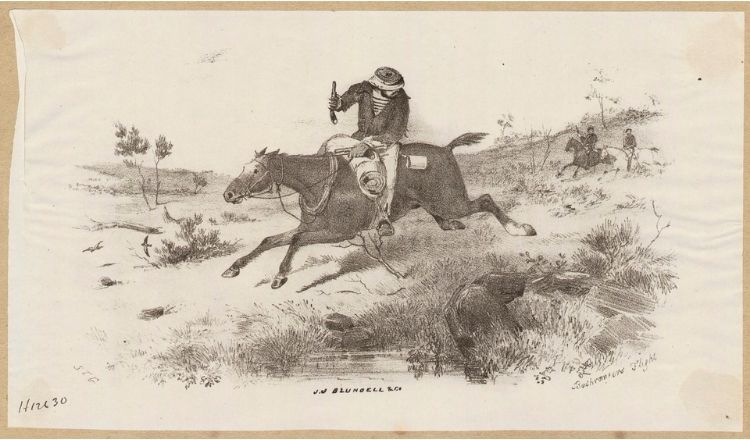

Gill, S. T., 1818-1880 artist.

Melbourne, Victoria : James J. Blundell & Co. ; [1856]

In preparation for writing this novel, I’ve also been using the National Library of Australia’s Trove website and the State Library of Victoria‘s online database. What rich resources they are! Newspaper articles, diaries, personal letters all contribute to a written landscape that I can draw on for this story.

So I immerse myself in texts of the time to help me get that language right for my future readers. But I still live in today and use the idioms of my own time when I log in to work, pop down to the shops or talk to friends. It’s no surprise that when I’m writing the novel the two timeframes get all mixed up inside me and bits of today leak into the landscape of 1874.

And as all you writers will know, when the words flow out of us in a writing session it’s not helpful to stop and worry about whether this phrase or that would have been used in the nineteenth century. So to help me get the language right, I use a tool called Google Ngram viewer brought to you by Google Books.

What is Google Ngram Viewer?

Google Ngram Viewer is a free tool that draws on a corpus of texts (fiction and non-fiction) so you can see and compare the usage of a word or phrase at a particular time and in a specific language variant.

How to use Google Ngram viewer

Here’s a little step by step for how to use Google Ngram viewer to get you started

- First, gather the words or phrases that you’re thinking about. If you have a couple in mind and want to choose which one was more popular at the your book’s action is taking place, that’s even better because ngrams allows you to compare.

- Go to https://books.google.com/ngrams

- You’ll see that It’s already set up to compare the use of the terms Frankenstein, Sherlock Holmes and Albert Einstein. (If it seems an odd choice to compare two fictional characters with a brilliant thinker from real life, I agree!)

- In the search bar, enter the word or phrase you want to check. If you’re comparing more than one, separate them with a comma (no spaces)

- Filter your search using the buttons below the search bar

- Choose the timeframe you want to check, or for a full picture of usage, leave it at the default range.

- Choose he corpus (database). As an Australian I generally choose British English, particularly as I’m writing about a time when the Americas were also developing their own take on English, with the Merriam Webster dictionary, and I want to search only texts that might include the language that was used by settlers of British origin.

- Select case-insensitive. I recommend this because capitalisation trends have changed over time. Choosing case-insensitive means it doesn’t matter where the writer who used the word or phrase you’re searching for put capital letters, it will still come up in your search.

- Leave smoothing as it is, unless you’re a data scientist. Google has set this to 3 and it gives you a line with some dips and peaks but not too distracting. You can change the smoothing if you’re drilling right down or wanting straight lines, but it’s probably not necessary for these kinds of searches.

6. And that’s it! There’s no search button as ngrams responds to your search and filter criteria as you add them.

Reasons to temper your enthusiasm

Google Ngram viewer is useful to check the odd phrase or word to ensure you’re not using anachronistic language, but be careful about trying to use it for serious academic research, and combine it with other tools to get the most out of it.

Not a suggestion machine

If you enter a phrase or word in to Google Ngram Viewer and it looks like it wasn’t being used in the period you’re researching, the tool doesn’t provide you with a suggestion. The way I deal with this is to flick between ngram and a thesaurus. If my term or word doesn’t show up as being in use during 1874, I pop over to an online thesaurus or (much more satisfyingly) my old, much-thumbed copy of Roget’s Thesaurus, and find an alternative to try in its place.

The original scans may be flawed.

OCR (Object Character Recognition) scanning isn’t perfect, although I will say it seems to be getting better all the time. This article about the limitations of Google ngram has a great example of the kinds of errors that can occur in scanning including a funny one about the F-word. If you’ve used Trove you’ll see those issues in action. The type in old documents from previous centuries can be blurry and damaged. In older documents, a letter shaped like lower case f appeared in places where modern text would use a lower case s and that creates its own systemic issues. An ‘untrained’ OCR scanner or an uncorrected scan could give inaccurate results if you’re searching for a word that might be systematically incorrect.

Rubbish in, rubbish out

A first principle of data analysis is that if your data set is flawed, the conclusions you draw will be flawed in the same way. Google Ngram Viewer is simply searching a database, and databases are only as good as the data that’s collected into them and the tools you can use to access that data. I’ve seen a few articles online that warn about the limitations of Google Books as a tool for studying languages and caution readers not to infer too much with a deep understanding of what makes up the data.

The gist of the message seems to be that you’d need to know what the corpus is made up of before deciding if Google Ngram viewer is useful as a way of analysing language for your project.

A potted history of Google Books

I will never forget the feeling in the pit of my stomach when I logged onto Google Books one day and found that my first novel was listed there. It had been scanned illegally by the search giant along with millions of other books, in what was clearly a rampant breach of copyright, making books that were still in copyright available in full, for free.

There were a class action and court cases. Google Books remains although if you go there now, you’re only able to see a snippet of copyrighted works.

The timing of Google’s actions was significant because it coincided with a period of upheaval and change in the publishing industry that was felt keenly in Australia.

For about ten years, between 2005-ish and 2016-ish the Australian publishing sector was worried about the combined impact of new technologies and the removal of parallel import restrictions. Google’s actions fed into that fear. Nearly every writers’ festival at the time seemed to feature a panel session with a title along the lines of ‘Is the book dead?’ and we all hoped it wasn’t but we all worried that maybe it was and none of us really knew what the future of reading and writing looked like.

Thankfully in 2022 we can say that the book is decidedly not dead. It’s going strong. In hindsight, we can all see that there’s been an impact but not always negative. And in line with my personal philosophy of life that ‘everything brings a gift’ the gift that Google Books has given writers is Google Ngram viewer.

Google Books is big data

More than a library, Google Books is a protected databank of millions of texts – fiction, non-fiction and academic – that is now used extensively in academia for research and the data is also available to writers like you and me. A corpus of 25 million books easily fits the definition of big data and that’s how Google Ngram viewer knows that this phrase or word was used more (or less) in 1874 than it was in 2019.

Let me know what you think!

If you’re a writer of historical fiction or non-fiction, I’d love to hear about how you keep the anachronisms out of your manuscript. And if you found this article about Google Ngram viewer useful I’d love to hear about that too!